Where do I start? It’s a question heard repeatedly in gardening webinars. Or maybe the question really is, how? When you’re contemplating a piece of ground you’d like to convert to a gardened space, how do you figure out which plants to select from the many thousands available? And how do you arrange those plants to create a design?

For practice, start with a manageable space. Create a design for a small garden bed, and you might be able to use it as a source of ideas for the rest of the landscape. Or, if conditions are appropriate, you can tie the larger design together by repeating the small bed’s grouping of plants in other parts of the garden.

As an example, imagine a 6′ by 10′ space, designated for perennials.

To determine the range of plants suitable for this plot, assess the cultural conditions by asking questions about the environment. Four basic questions are:

- How much sun does the plot receive?

- After rain or watering, does the soil dry out quickly and remain dry, drain easily but retain some moisture, or drain slowly and rarely dry out?

- In which plant hardiness zone is the plot located? The hardiness zone indicates the average annual coldest temperature for a location and is used to identify plants that will survive.

- Where on the property is the plot located? Is it a foundation planting (next to a building), an island bed, or part of a perimeter planting?

The next questions are about the characteristics for this particular planting:

- What is the preferred bloom period for the flowering plants in the plot?

- What are the color preferences for the blooms?

- Will the mix of plants include:

- Ornamental grasses?

- Plants that attract bees, butterflies, moths, and other pollinators?

- Native plants, and if so, are cultivars acceptable? Cultivars are plants with features deliberately selected to change or enhance what is found in the wild, such as flower color.

With these questions answered, consider shapes and heights, which might be:

- Tall, medium, short

- Upright, mounded, trailing

- Wild, semi-wild, contained.

Returning to the example, our 6′ by 10′ plot:

– Is in full sun

– Has good drainage

– Is located in hardiness zone 7A, and

– Is a foundation planting in front of the house.

For plants, we would prefer:

– Perennials that bloom from spring through late fall (May into November, if possible)

– A mix of red and yellow blooms, perhaps with purple as a contrast

– At least one type of ornamental grass

– Pollinator-friendly selections

– At least half of the plot to be filled with native cultivars or other native selections, and

– A design that combines control with a bit of wildness.

Having decided on characteristics, we can begin to imagine plant shapes and arrangement. A simple and traditional design for a foundation planting, which can be viewed only from the front or side, is to start with a tall plant in back, a medium height plant in the middle, and shorter plants in front.

The tall plant will be closest to the foundation and probably will have the most contained shape, with its verticality emphasized.

A mounded middle plant will provide contrast with the tall plant. Or if not mounded, try a shorter upright plant with stems that bend out to the sides, vase-like.

In the front could be a mix of heights and shapes, with lower mounding plants, trailing plants, and short upright plants.

Plant identification—the research phase of this process—comes next, using plant databases to match cultural conditions with plant characteristics.

For this perennial bed exercise, four databases come to mind as potentially useful. The Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder covers native and nonnative plants and provides search criteria including plant type, zone, sun, water, color, and bloom time. Another source with numerous search criteria is the University of Connecticut Plant Database. The Mt. Cuba Center Trial Garden publishes detailed evaluations of native plants and their cultivars, and the Native Plant Database maintained by the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center allows filtering by states and a variety of plant characteristics.

It’s tempting to jump into searching, especially with such interesting resources, but a little preparation can prevent the process from becoming overwhelming. My preference is to use a checklist to record answers to the questions about cultural conditions and characteristics.

To keep track of plants identified, I use a spreadsheet that includes the criteria from the checklist plus additional features such as the height of each species and the recommended spacing for planting.

With the plants identified, there’s enough information to create a layout for the space, or multiple layouts showing different configurations. You can follow the arrangement described above (starting in the back of the plot and moving forward with tall, mounded, and short upright plants) or the plants identified may suggest their own arrangement:

- Use graph paper, drawing paper, or design software to sketch the 6’ by 10’ perennial bed footprint, noting the scale (1/2” equals 1’, for example)

- Choose a method to fit the design pieces—the plants—together:

- Sketch possible groupings, in detail if you can or using circles, ovals, and other simple shapes to represent clusters of plants

- Place stakes in the plot to represent the plants and photograph the layout

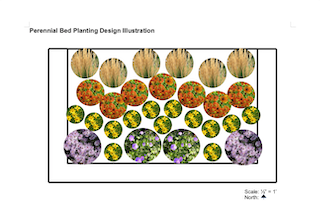

- Assemble a digital illustration, with photos of the plants superimposed on the footprint (see below)

- Determine the number of plants for each part of the design, using the spacing information already recorded or planting calculators available online.

The design is ready for implementation and, most likely, modification. Plants carefully identified may not be available, requiring substitutes to be found; growing conditions may not be as suitable as expected, causing plants to fail; and the design that looked great on paper may evolve in a year or two to a jumble that requires cutting back and rethinking.

It is this evolution that is one of the more challenging but also rewarding aspects of planting design. Time is a design element, and as plants grow, the design changes. Understanding how plants interact and affect a design over the seasons is essential knowledge, gained from experimentation and experience, over time.

And if over time the design works, you can duplicate it elsewhere in the garden or use a rearranged version — imagine Calamagrostis surrounded by rings of Helenium, Coreopsis, and Geranium in an island bed, for example, or Asters and Coreopsis combined to cover the sunny sloping edge of a larger garden bed.

Where to start? Start small and build.